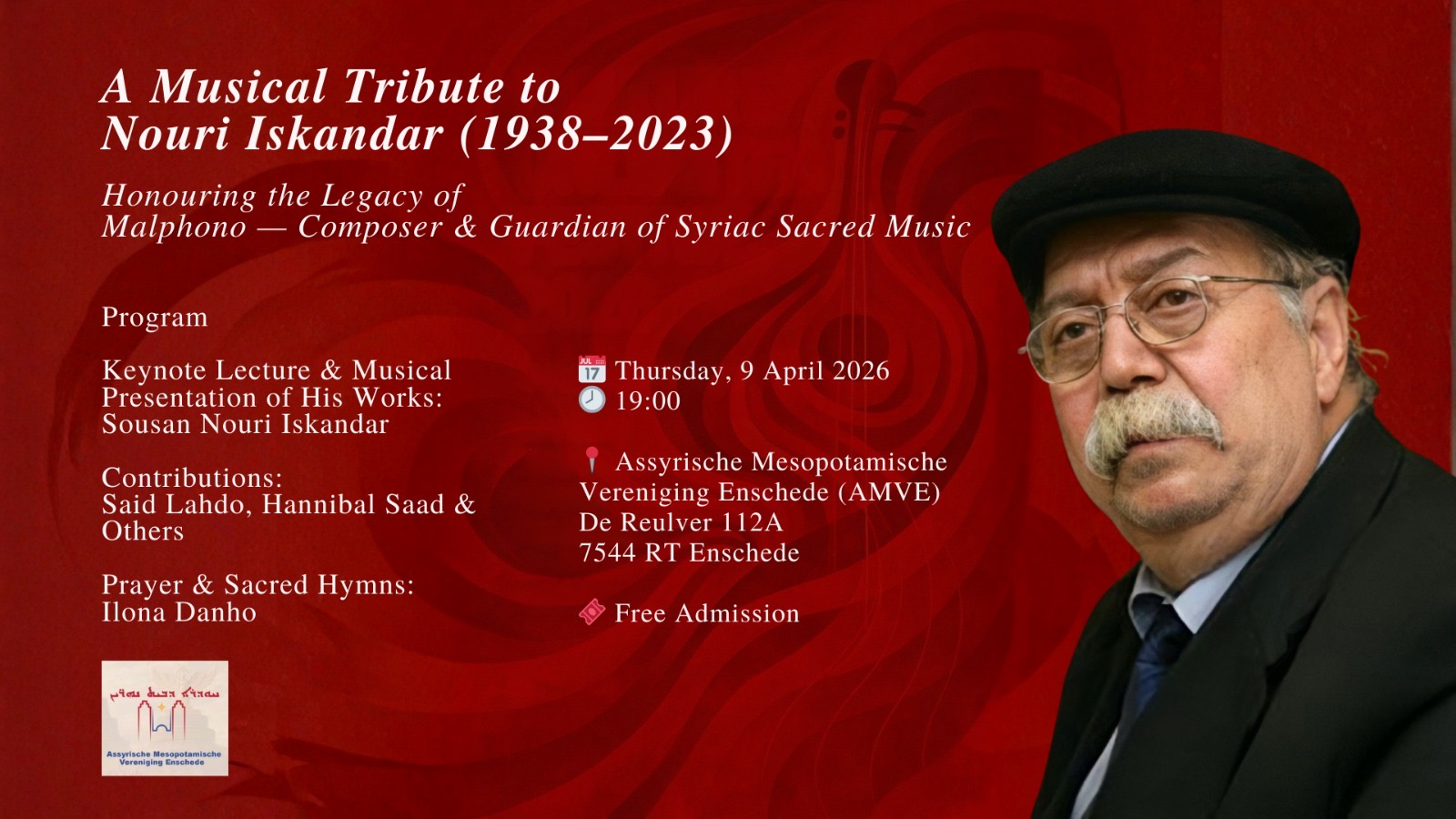

A Musical Tribute to Malfono Nouri Iskandar (1938–2023)

A Musical Tribute to Malfono Nouri Iskandar (1938–2023)

We warmly invite you to join us in honoring the life and legacy of

Malphono Nouri Iskandar — composer, researcher, and guardian of Syriac sacred music.

Throughout his life, he devoted himself to preserving, documenting, and transmitting Syrian and Syriac church musical heritage. With deep dedication, he contributed to sustaining this spiritual tradition and giving it renewed meaning for future generations.

This evening is dedicated to remembrance and tribute, featuring lecture, reflection, prayer, and music in honor of his enduring legacy.

Programme

Keynote Lecture & Musical Presentation of His Works:

Sousan Nouri Iskandar

Contributions

Said Lahdo, Hannibal Saad and others

Prayer & Sacred Hymns

Ilona Danho

📅 Thursday, 9 April 2026 – 19:00

📍 Assyrian Mesopotamian Association Enschede (AMVE)

De Reulver 112A – 7544 RT Enschede

The Netherlands

Free Admission

Malfono Nouri Iskandar (1938–2023)

Composer, Researcher, and Architect of Contemporary Syriac Music

Malfono Nouri Iskandar occupies a singular position in the history of modern Syrian and Syriac music. He was not merely a composer, nor only a researcher or educator; he was an intellectual architect of musical renewal, a figure who understood that preservation without transformation leads to stagnation, and that innovation without roots leads to dissolution. His life’s work unfolded precisely within this delicate balance.

Born in Deir al-Zur in 1938 and later shaped by the rich musical climate of Aleppo, Iskandar grew up within the living soundscape of Syriac liturgical chant. As a young deacon in the Syriac Orthodox Church, he encountered the profound melodic treasury of his tradition — melodies that had survived for centuries through oral transmission, yet were increasingly at risk of neglect or simplification. This early exposure awakened in him not only devotion, but inquiry. He recognized that sacred music carried within it an entire historical consciousness, a theology of sound, and a system of modal thought that required both protection and reinterpretation.

His academic formation at the Higher Institute of Arabic Music in Cairo, where he graduated in 1964 with a degree in Musical Education, deepened his theoretical and structural understanding of oriental music. Yet his vision extended beyond academic certification. He began asking fundamental questions about the future of oriental composition. Could the maqam system evolve without losing its essence? Could Syriac sacred music be documented without being stripped of its spiritual depth? Could oriental music develop complex structures comparable to symphonic forms while preserving its modal identity?

These questions guided him for the rest of his life.

Over nearly two decades, Iskandar dedicated himself to the systematic research of Syriac spiritual music. He documented and analyzed hundreds of liturgical melodies rooted in the traditions of the ancient schools of Raha (Edessa) and Deir al-Zaafaran. His scholarly work resulted in major publications, including Bayt Kazoo – The Tradition of Rahwiya Tunes and Bayt Kazoo – The Tradition of Deir al-Zaafaran and Its Followers. These volumes stand as monumental contributions to the academic understanding of Syriac sacred music, transforming fragile oral memory into structured, enduring knowledge.

But Iskandar did not see research as an act of preservation alone. He believed that sanctifying heritage without allowing it to develop creates a dangerous divide between listeners and their own inherited music. When tradition becomes untouchable, it ceases to breathe. For him, the task was not to freeze Syriac music in its historical form, but to allow it to evolve organically, guided by deep knowledge rather than superficial imitation.

One of his most significant technical contributions lay in his exploration of polyphony and harmony within the framework of the oriental maqam. He recognized a fundamental problem: when Western harmonic systems are applied mechanically to Eastern modal structures, the spirit of the maqam is often lost. The quarter-tone inflections, the subtle melodic tensions, and the spiritual character of the mode become flattened under rigid harmonic grids.

Iskandar sought a different path. Influenced in part by his studies in Aleppo with the Syrian jazz musician Fatishe Hermian, he began experimenting with written compositional forms that rose from the maqam’s internal logic rather than imposing foreign systems upon it. His work involved analytical study of polyphony and harmony, but always in relation to the tonal character of the oriental mode. He explored harmonic blends that could coexist with quarter-tone structures, seeking dramatic and dynamic musical dialogue rather than harmonic domination.

His aim was not Westernization. He did not seek to produce oriental music that resembled European symphonic writing. Rather, he envisioned a contemporary oriental compositional language capable of intellectual and philosophical depth — a music in which poetry, thought, and spiritual inquiry could inhabit expanded formal structures without sacrificing modal identity.

In this context, he often reflected on the example of the Aleppan Qudud, whose roots are intertwined with Syriac chant. For Iskandar, these songs illustrated how a living tradition could enter stagnation when it ceased to develop structurally. He believed that renewal required courage: the courage to reinterpret, to compose anew, to engage critically with heritage rather than merely reproduce it.

His compositional output reflects this vision. Works such as Oud Concerto and String Trio demonstrate his efforts to recreate oriental maqamat within contemporary chamber forms. Recordings like Revelations and Vision represent the culmination of his blending of oriental modality with structured compositional technique. In Dialogue of Love (1995), he created a synthesis of Islamic devotional chants and Syriac hymns, revealing their shared modal and spiritual foundations. His orchestral and choral setting of the poem Khattama further illustrates his ability to integrate literary expression with expanded musical architecture.

Even in his theatrical and later works — including music for Bacchus’ Slaves, Moans (2003), and The Giver of Love: An Introduction to Sufism (2007) — one perceives the same central concern: how to create new musical forms that allow oriental thought to unfold dynamically, without collapsing into imitation.

Beyond composition, Iskandar was an educator and institutional leader. From 1989 onward, he taught in schools and teacher training institutes in Aleppo. Between 1996 and 2002, he directed the Arab Institute of Music in Aleppo, shaping generations of musicians. He also founded and directed choirs, most notably “Qowqweyo – Al-Fakharoon,” which performed Syriac Orthodox liturgical repertoire both in Syria and in European capitals, extending the presence of Syriac chant beyond ecclesiastical boundaries.

Throughout his life, he received recognition from local and international cultural institutions, including honors at the First International Forum for Oriental Music – Oriental Landscapes in 2009. Yet awards were secondary to his mission.

Nouri Iskandar was, above all, a thinker of sound. He preserved ancient melodies, but he also challenged them to speak anew. He confronted the technical problems of maqam and harmony with intellectual seriousness. He refused both blind imitation of the West and blind sanctification of the past. Instead, he pursued a third path — one in which tradition and modernity enter into creative dialogue.

His legacy is not only in recordings, publications, or compositions. It lies in the method he embodied: research grounded in devotion, innovation grounded in knowledge, and composition grounded in philosophical inquiry.

In him, Syriac sacred music found not only a guardian, but a visionary.